OK, so despite all the doom and gloom of my last but one

post (here), I have now been working at Imperial College London for the last

week. We have finally escaped Norfolk, breaking the ‘If you stay for 5 years,

you stay forever’ rule.

I’m employed as a ‘Research Associate in Organic Matter and

Minerals of Mars’, my job is to look for ways to improve our chances of

detecting organic matter for future Mars lander missions. Put simply, I’m

helping to LOOK FOR LIFE ON MARS (cue some Bowie)!

To sum up the problem I’ll be working on, as I understand it

so far (remember, I’m not a chemist): Mars landers have not yet discovered conclusive

evidence of organic matter (note: organic matter does not necessarily mean

biological matter, they are compounds containing carbon and usually C-H and/or

C-C bonds) but have found evidence of a group of minerals called perchlorates

(ClO4) being pretty ubiquitous in Martian lake sediments (e.g. Glavin et al., 2013). These

sediments are also the places we would expect to find evidence of organic

matter, through its concentration by fluvial and lacustrine sedimentation

processes. We know that there should be a measurable concentration of organics

delivered to the Martian surface by meteorites and certain compounds could

indicate evidence of past or current alien life, but nothing has been found so

far. We believe that it is the presence of perchlorate that is currently

blocking the positive identification of organic matter.

Analysis of Martian sediments for organics is carried out by

pyrolysis gas chromatography mass spectrometry (Py-GC-MS). The sample is heated

in the absence of oxygen to break down large molecules into smaller ones which

can be separated by gas chromatography and detected by mass spectrometry, the

products tell us what the big molecules originally were. The issue here is,

perchlorate is strongly oxidising; it is a bleach. When it is heated in the pyrolysis

unit as part of the sample, it breaks down releasing oxygen and chlorine. The

presence of oxygen causes any organic matter present to combust, being lost as

carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and water. With everything breaking down and

combusting, we do not detect either the organic matter or the perchlorate by

this method – so it took a long time for anyone to even realise there was a

problem.

Along with the rest of the research group, I now have to

figure out a way to make this less of a problem, hopefully in time for ExoMars2020…

So far I’ve been reading up on the last 40 years of

geochemical analysis on Mars trying to get my head around the problem and

understand a bit of the chemistry, which is fun as I haven’t done any organic

geochemistry since my Masters.

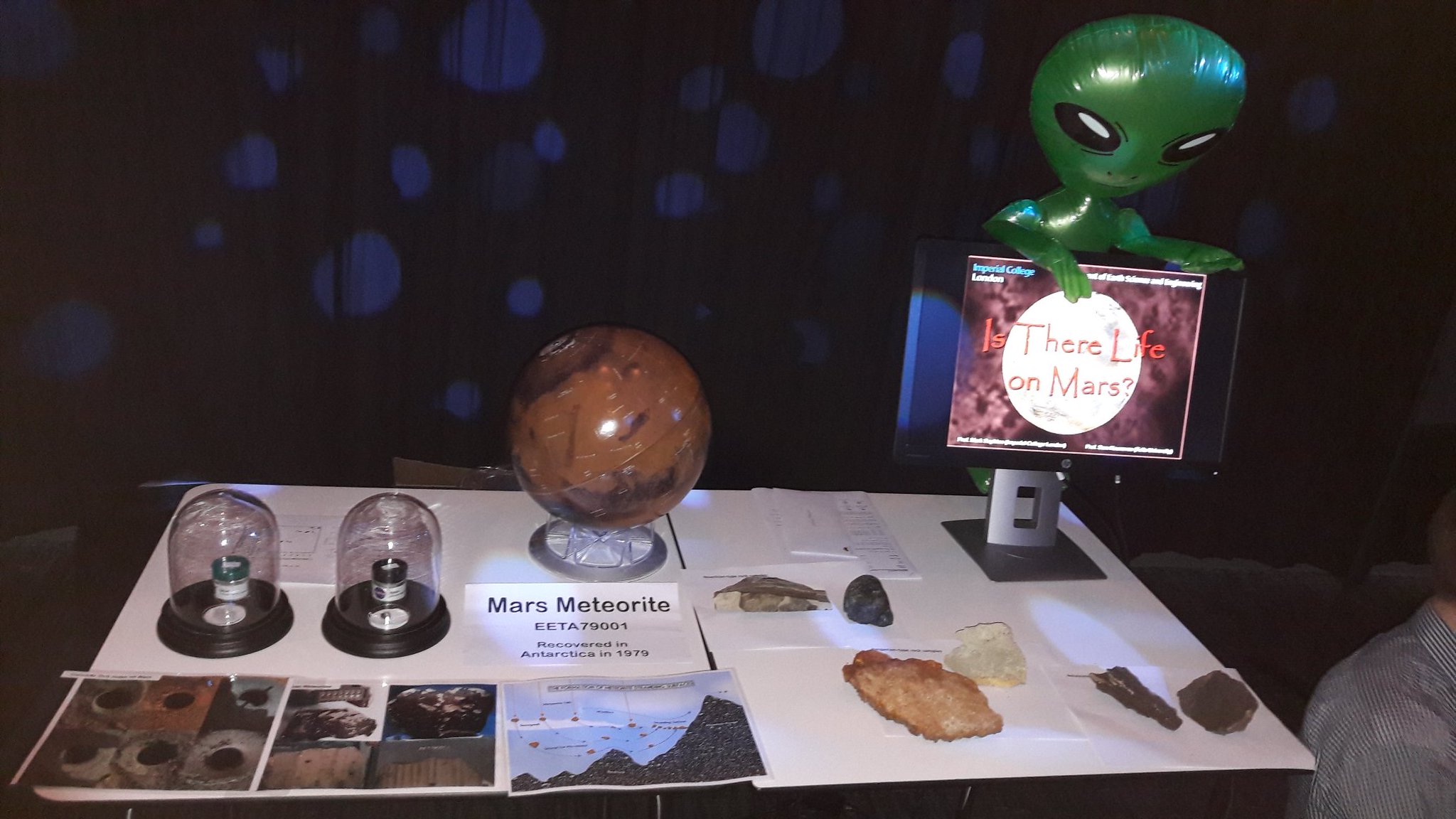

On Friday I got sent to an outreach event across the road at

the Royal Albert Hall, showing kids some bits of actual Martian meteorite and

talking about the various ages of Mars, using Earth analogue rocks to

demonstrate the strata which were laid down during each period. However, the

guy next to us who’d brought a replica space suit to try on proved more popular

for some reason.

This was all part of a big school event which culminated in

the Royal Philharmonic playing the planets, which was a pretty cool way to

spend a Friday afternoon. It was good to hear that I am studying the planet with

the best soundtrack.

Next week I’ll actually get to grips with the machine I’ll

be mostly working on (the Py-GCMS) and will be thrown in at the deep end

analysing irreplaceable Apollo 17 moon rocks, so let’s see how that goes…

I think this project is going to be a bit more interesting

than the snails…

No comments:

Post a Comment