Here’s an early Christmas present for everyone (so both of

you who read this blog), our latest paper (my first out of this project) is now

published online and completely open access for anyone to read.

If you can’t be bothered to read it, here is a summary:

Since the Viking landers back in 1976, numerous missions

have gone to Mars and attempted to find organic matter on the surface. However,

to this date, none have succeeded in finding anything other than simple

chlorinated hydrocarbons. We expect there to be a detectable amount of relatively

complex organic molecules in the Martian near surface from meteoritic input

(meteorites are full of organic matter), hydrothermal processes and maybe even

left behind as evidence of extinct (or, unlikely but not impossible, extant)

life. This lack of detectable organics was always a bit of a mystery…

Note: the presence of organic matter does not necessarily

mean the existence of life, organic molecules are just those which have

carbon and hydrogen and they can be formed by numerous non-biological processes

– including in deep space.

However, since they were accidentally discovered by the

Phoenix mission back in 2008 we’ve known that that there are these salts on

Mars called perchlorates. These salts are very rare on Earth, only being known

to exist in significant quantities in the Atacama Desert and the Antarctic Dry

Valleys; two of the driest places on Earth. As the name suggests perchlorates have 4

oxygens to each chlorine ion and so are very highly oxidising. While (relatively)

stable on the Martian surface, as soon as these are heated within the sample

analysis oven of a Martian lander or rover these literally explode, giving off

loads of oxygen into the analytical system (which should be a vacuum). This

means that any organic matter which may be in the Martian soil is combusted,

reacting with the oxygen present and breaking down to carbon dioxide and carbon

monoxide, and the few surviving scraps

are heavily broken up and react with the chlorine in the perchlorate, making small

chlorinated hydrocarbons. Because of this destruction the molecules we are

interested in cannot be detected – This is the perchlorate problem.

|

| My attempt to summarise the Perchlorate Problem on the Sketch Your Science wall at AGU this year |

My job as a postdoc researcher at Imperial College is to

attempt to find a way around this ‘perchlorate problem’ by researching how

these perchlorates (and other similar minerals) react with organic matter.

The first step of this, however, is to try to understand a little more about

the Martian perchlorates themselves. And this is what this recently published body of work

was concerned with.

Since it landed on the Mars in 2012 the Curiosity Rover has drilled 15 holes into the Martian surface and analysed the drilled sample to see what it is made of. One of the techniques used is looking at the gases given off by the sample when it is heated. However, every time the Curiosity Rover has analysed one of these sample

holes, the temperature that oxygen gas is released from the sample is very different (Sutter et al., 2016). Most of the oxygen given off is believed to have come from these perchlorates (based on other gases given off at the same time). It has been found by previous laboratory

experiments that different types of perchlorate salts (magnesium perchlorate,

iron perchlorate, calcium perchlorate, etc) break down and give off oxygen at

different temperatures (Glavin et al., 2015), and also break down at different temperatures depending

on whether other minerals which may act as catalysts are also present in the

soil (Sutter et al., 2014). Therefore it has so far been concluded that different types of perchlorates

and/or catalyst minerals have been present at each drill site.

|

| Curiosity on Mars (credit: NASA) |

|

| The first 14 drill holes Curiosity drilled on Mars (credit: NASA) |

This is a bit problematic. It is believed that most

perchlorate forms in the Martian atmosphere and falls out onto the surface (as

it does on Earth) and so there is no known mechanism for having different

perchlorates in different places – they should all be pretty much the same

across the Martian surface.

It is known that perchlorates are highly hydrophilic – they

will suck up any water available (they are used as drying agents in industry)

and can change their hydration state (how many molecules of water are bound to

each molecule of perchlorate) really easily. The temperature and humidity of

the Martian surface changes massively throughout the Martian day and year. Photographs

taken on Mars by Phoenix show growing blobs on the lander struts which have

been interpreted as perchlorate goos as they absorb water throughout the

Martian day. So, my boss, Mark Sephton, had an idea that the hydration state of

the perchlorates may actually have an important effect on their breakdown

temperature and set me to investigate this.

|

| 'Blobs' of perchlorate 'goo' moving across the struts of the Phoenix lander (Renno et al., 2009) |

I did this by taking a single one of the perchlorate salts (magnesium perchlorate) and drying it out in the glassware drying oven to drive off water in an attempt to reduce its hydration state. After three weeks I removed some sample, flash heated it and analysed the gases given off using pyrolysis-GCMS at 100 °C temperature steps from 200-1000 °C to create oxygen (and other lesser gases) release-temperature profiles. A sample of the perchlorate was also left out on the lab bench to rehydrate and analysed in the same way after 24, 48 and 72 hours of exposure and rehydration. This whole experiment was repeated after another week and then after a fortnight so oxygen release profiles were created for 3, 4 and 5 week drying times and corresponding 24, 48 and 72 hour re-exposure samples.

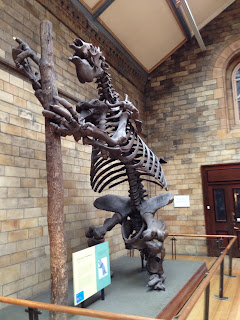

It was confirmed that these drying and re-exposure

experiments were definitely changing the hydration states of the perchlorates

by testing them (by X-ray diffraction) next door in the Natural History Museum.

This involved transporting them through crowds of tourists under an inert

atmosphere (in a sealed lunchbox filled with nitrogen gas) to prevent further

hydration state change.

What we found was that different hydration states did indeed

affect the temperature of decomposition so that the oxygen release profiles

were as different for different hydration states of this one kind of perchlorate

as the previous studies had found for all the different kinds they tested.

This, therefore, gave a much simpler answer to this puzzle: Curiosity has been analysing

different samples with different hydration states of perchlorate in them. This

makes sense as the different samples drilled have been analysed at different

times of the Martian day and year and samples spend varying amounts of time stashed

inside the temperature-controlled innards of the rover before they get round to

being analysed – which could allow further changes in their hydration state.

Our data show that is it possible for numerous hydration states of perchlorate

to exist within a sample and this leads to multiple peaks in the oxygen release

profile, some of the Martian samples have multiple peaks in their oxygen

release profile and so we suggest that this is due to unstable mixtures of

perchlorate hydration states being present on the Martian surface.

|

| This figure from the paper shows how the data from this study (A) compares to select samples analysed on Mars by Curiosity (B) and various types of perchlorate from a study by Glavin et al. (2015) (C). It can clearly be seen that the variation in the samples of magnesium perchlorate that were dried out for various numbers of weeks and analysed in this study is almost as great as the variation in different perchlorates from the Glavin et al. study. So, different hydration states may offer a simpler explanation for the variation seen in the Martian samples. |

We tried to see if the oxygen release profile of the Martian

samples (and therefore, based on our findings, the perchlorate hydration state)

corresponded to the climate conditions at the time they were sampled at but did

not find any relationship. There did seem, however, to be a vague suggestion in

the data that they were related to the time of the year that they were sampled

at, although more data would be needed to be sure about this.

All in all, we conclude that the hydration state of

perchlorate salts is yet another thing to make making sense of Martian data yet

more complicated.